This is (not) my land

Land Acknowledgement | giving thanks

I would like to acknowledge that I am on the traditional land of the first people of Seattle, the Duwamish People past and present, and honor with gratitude the land itself and the Duwamish Tribe.

View from the top of the hill by my house, August 2023

This week, in the United States, millions of people will gather with family and friends to celebrate Thanksgiving. For a smaller subset of Americans, including the Native peoples of this land, the fourth Thursday in November is otherwise known as the National Day of Mourning.

I have been thinking of adding a land acknowledgement to my website for a long time. I admit that one reason I have failed to do so already is simply forgetfulness — being a very white person, it is easy for me to forget — but another reason is that I hesitate to appear as if I am making a token acknowledgement without deeper contemplation. (It is also true that I trip sometimes trying to find the “right” words, and worry I may accidentally say the wrong thing, but I believe it is better to try—and keep learning—than to say nothing at all.)

However, as the Duwamish tribe points out, “It is important to note that this kind of acknowledgement is not a new practice developed by colonial institutions. Land acknowledgement is a traditional custom dating back centuries for many Native communities and nations. For non-Indigenous communities, land acknowledgement is a powerful way of showing respect and honoring the Indigenous Peoples of the land on which we work and live. Acknowledgement is a simple way of resisting the erasure of Indigenous histories and working towards honoring and inviting the truth.” (www.duwamishtribe.org)

To that end, I would like to acknowledge that my family is privileged to own a home in Kirkland, WA, just outside of Seattle. Home ownership carries not only complicity with the capitalist system and an imperialist mindset that land can even be “owned,” but the forcible removal of Native people from their lands, with or without treaties or even acknowledgement from the federal government. My family and I reside on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded lands of the Duwamish people, and this specific land may also have been part of the traditional territory of the Cayuse, Umatilla, and Walla Walla peoples, who primarily reside in the Columbia Plateau region of what is now northeastern Oregon. We are immediately surrounded by territories of other Coast Salish-speaking tribes including the Snohomish, Snoqualmie, Muckleshoot, and Tulalip.

You can visit native-land.ca to find out more about the Native territories you reside on, and I encourage you to visit your local tribal cultural centers to learn more about your region’s land, history, traditions, and present-day Native communities and cultures.

I truly cannot describe the awe and appreciation I have felt in such places, learning about the ancestral lands I grew up on (Miwok, Me-Wuk/Northern Sierra Miwok, and Plains Miwok territory in California), and places I have visited, from the Hibulb Cultural Center and Natural History Preserve of the Tulalip Tribes to the Makah Cultural & Research Center Museum in Neah Bay. Each time I visit a Native cultural institution in person, I feel honored and grateful to be sharing space across time with the many, many, generations that have been there before me. I learn so much, including something that can’t quite be put into words — something new about living in communion with the earth, instead of treading upon it without a thought. Our homes, yards, workplaces, schools, and streets are bursting microcosms of nature, rich environments of flora, fauna, and interconnections between species, climate, and time — what Jenny Odell refers to as “bioregionalism” in How to Do Nothing. I return to my daily life, lands, and habits forever changed.

As a white person (of primarily Western European descent), something has always ached inside me to feel connected and grounded to the earth, place, and ancestors that feel lost and disconnected. I never quite know where I’m from, or where I belong, and I feel ashamed for feeling that way because it is not my people that were stolen from their lands, or had their lands stolen from them — yet this severing still haunts me. Every Thanksgiving, I do feel grateful for being with friends, family, and abundant food, but I also remember the erasure, appropriation of, and violent genocide of Native American peoples. I am so grateful that it did not fully succeed—they are still here. And so often, despite everything, still willing to share knowledge and healing with us. We, in our humanity, are still here — all of us who believe we can grieve and give thanks at the same time.

Time/Space, backyard environmental art, Kirkland WA, April 2024

“Crib Decay” photograph from time-lapse decay project, April 2023.

This is (not) my land

that my house sits upon

that my family lives on

Where my toddler collects pine cones,

rocks,

purple leaves.

This is not my land

That keeps me entranced

With it’s spider’s webs

and winds and rains

The dew on the dandelions

The robin’s chit chit

The roots that go deep.

Yet this Land

is a part of me -this place of soaring mountains

sunsets over lakes and seas.

It teaches me to see.

— Alexia Casiano, October 2023

View from the top of the hill, one block from my house, Kirkland WA - April 2023

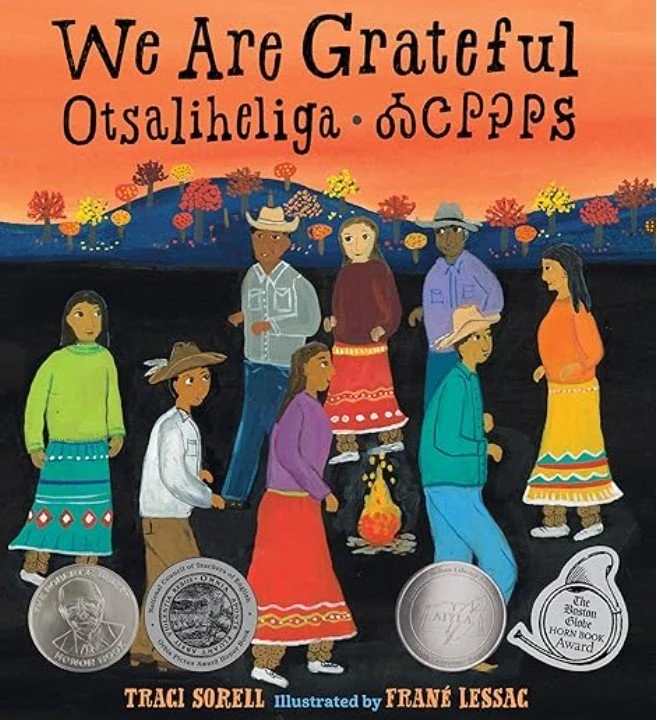

This is my current favorite children’s book about Thanksgiving, which isn’t about the holiday of American Thanksgiving at all, but rather a Cherokee story about gratitude throughout each season. What’s your favorite book about Native American traditions, culture, or correcting the narrative of Thanksgiving?